iOS Engine Choice In Depth

Recent posts here covering the slow pace of WebKit development and ways the mobile browser market has evolved to disrespect user choice have sparked conversations with friends and colleagues. Many discussions have focused on Apple's rationales, explicit and implied, in keeping the iOS versions of Edge, Firefox, Opera, and Chrome less capable than they are on every other platform.

How does Apple justify such a policy? Particularly since last winter, when it finally (albeit haltingly and eventually) became possible to set a browser other than Safari as the default?

Two categories of argument are worth highlighting: those offered by Apple and claims made by others in Apple's defence[1].

Apple's Arguments #

The decision to ban competing browser engines is as old as iOS, but Apple has only attempted to explain itself in recent years. I'm only aware of a few such instances:

- Apple's 2019 response to the U.S. House Judiciary Committee's Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law (PDF)

- Apple's February 2021 response to the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (PDF)

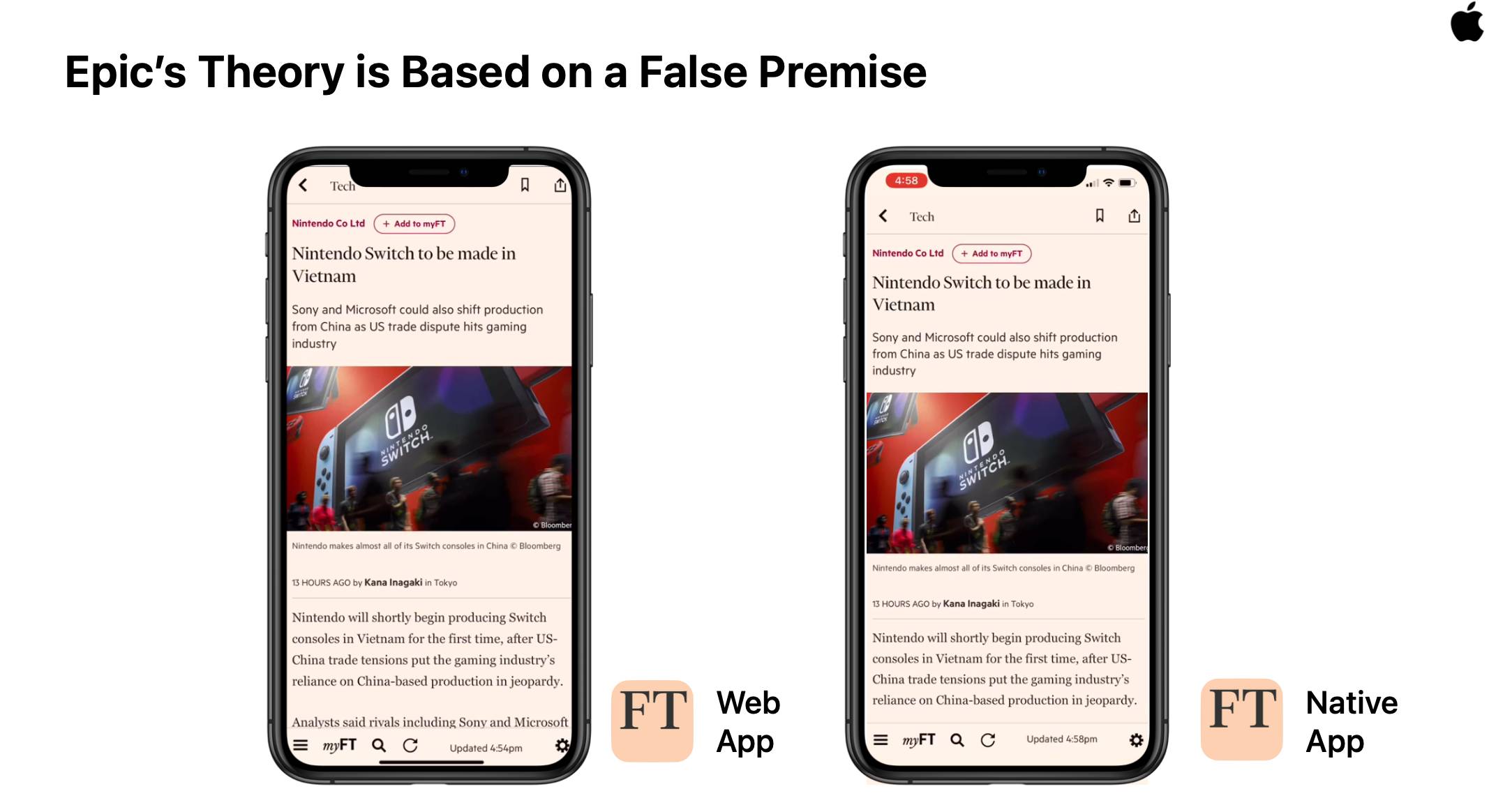

- 2021 court arguments in the case of EPIC Games vs. Apple (slide image)

Experts tend to treat Apple's arguments with disdain, but understanding why isn't instantly apparent to a non-technical audience. Apple's response to the U.S. House Antitrust Subcommittee includes their most specific responses to the set of claims:

4. Does Apple restrict, in any way, the ability of competing web browsers to deploy their own web browsing engines when running on Apple's operating system? If yes, please describe any restrictions that Apple imposes and all the reasons for doing so. If no, please explain why not.

All iOS apps that browse the web are required to use "the appropriate WebKit framework and WebKit Javascript" pursuant to Section 2.5.6 of the App Store Review Guidelines <https://developer.apple.com/app-store/review/guidelines/#software-requirements>.

The purpose of this rule is to protect user privacy and security. Nefarious websites have analysed other web browser engines and found flaws that have not been disclosed, and exploit those flaws when a user goes to a particular website to silently violate user privacy or security. This presents an acute danger to users, considering the vast amount of private and sensitive data that is typically accessed on a mobile device.

By requiring apps to use WebKit, Apple can rapidly and accurately address exploits across our entire user base and most effectively secure their privacy and security. Also, allowing other web browser engines could put users at risk if developers abandon their apps or fail to address a security flaw quickly. By requiring use of WebKit, Apple can provide security updates to all our users quickly and accurately, no matter which browser they decide to download from the App Store.

WebKit is an open-source web engine that allows Apple to enable improvements contributed by third parties. Instead of having to supply an entirely separate browser engine (with the significant privacy and security issues this creates), third parties can contribute relevant changes to the WebKit project for incorporation into the WebKit engine.

It's worth assessing these claims from most easily falsified to most contested.

Apple's Open Source Claim #

The open source nature of WebKit is indisputable as a legal technicality. Anyone who cares to download and fork the code can do so. To the extent they are both skilled in browser construction and endowed with the freedom to distribute binaries with modifications, the WebKit project can serve as the basis for modified engines of all sorts, fulfilling the chief rights and liberties guaranteed by open source licensing.

Apple, however, goes further in this claim, asserting that the open source nature of the WebKit project extends to open governance regarding feature additions. Apple must know this is misleading.

Presumably, Apple's counsel included this specious filigree to distract from the reality that half of the conditions necessary for driving progress through open source are foreclosed by iOS policies preventing browsers from shipping their own engines.

Anyone can modify WebKit, but the chances of Apple actually accepting changes to their engine are, historically, relatively low — and here I speak from experience.

From 2008 to 2013, the Chrome project was based on WebKit, and a growing team of Chrome engineers began to contribute heavily "upstream." The eventual Blink fork was precipitated by an insurmountable difficulty in doing precisely what Apple suggested to Congress: contributing code upstream to WebKit to enable new features.

Far from being straightforward, the differing near-term objectives of browser teams ensure that potential additions are contentious. Project owners are territorial, fiercely guarding the integrity of their codebases. Until and unless they become convinced of the utility of a feature, "no" is the usual response.

Large projects like browser engines also exercise governance through a hierarchy of "OWNER bits," which explicitly name engineers empowered to permit changes in a section of the codebase. There tend to be very few experts in each area versus the number of engineers attempting to contribute code, and sign-off of an OWNER is frequently required before the project accepts changes.

For example, OWNERs and experts in video and audio codecs can agree to extensive changes in their domain but cannot green-light changes in areas such as layout, networking, storage, or JavaScript engines. The collaboration required to approve changes in an area can quickly look like a drain or tax on scarce resources better spent elsewhere, at least from the perspective of a company employing these very senior engineers. If the organisation finds its most senior engineers are spending a great deal of time reviewing code for features they have no interest in — and may "flag off" in their own products[2] — it becomes inevitable that managers will communicate disinterest. The pace of reviews needed to finish a feature in this state can taper off or dry up completely, frustrating collaborators on both sides.

This was exactly the experience of Chrome while developing Web Components.

When browsers provide integrated engines (an "integrated browser"), then it's possible to disagree in standards venues, return to one's corner, and deliver (hopefully and responsibly) the best design to developers. Developers can provide feedback from using features and lobby other browsers to adopt (or re-design) them. This process can be messy and slow, but it never creates a political blockage for developing new capabilities for the web.

WebKit, by contrast, has in recent years gone so far as to publicly state that they pre-emptively "decline to implement" a veritable truckload of useful new features that some browser vendors feel are essential to the future of productivity on the web.

The signal to parties who might contribute code for these features could scarcely be clearer: your patch is unlikely to be accepted.

Suppose by some miracle a "controversial" feature is merged into WebKit. Such features have lingered behind feature flags for years, never to be flagged on by default in Safari or even made available to competing iOS browsers.

When priority disagreements inevitably arise, alternative iOS browsers cannot even demonstrate through contributions to WebKit that a feature is safe or well received by web developers on iOS. Potential contributors won't dare the expense of an attempt. Apple's opacity and history of challenging collaboration have done more than enough to discourage adventurous developers.

Other mechanisms for extending features of third party browsers may be possible (and in some areas, with low fidelity on iOS; more on that below), but contributions to WebKit are not a viable path for a majority of potential additions.

It is both shocking and unsurprising that Apple felt compelled to mislead Congress on these points, given the facts are not in their favour and few legislative staffers have enough context to see through a browser internals smoke screen.

Apple's Security Argument #

The most convincing argument in Apple's 2019 response to the U.S. House Judiciary Committee is rooted in security. Apple argues it bans other engines from iOS because:

Nefarious websites have analysed other web browser engines and found flaws that have not been disclosed, and exploit those flaws when a user goes to a particular website to silently violate user privacy or security.

Like all browsers, WebKit and Safari are under constant attack, including the construction of "zero day" attacks that Apple insinuates WebKit is immune to.

As a result of this threat landscape, responsible browser vendors work to put untrusted code (everything downloaded from the web) in "sandboxes"; restricted execution environments that are given fewer privileges than regular programs. Modern browsers layer protections on top of OS-level sandboxes, bolstering the default configuration with further limits on "renderer" processes.

Some engines go further, adopting safer systems languages in their first lines of defence, or using a larger number of sandboxes to strictly isolate individual websites from each other. Thanks to Apple's policy, none of these protections were in place for iOS users in the most recent Solar Winds incident, not even folks who use browsers other than Safari. The beefy devices Apple sells provide more than enough resources to raise such software defences, yet iOS users are years behind for no other reason than Apple's own under-investment in — and disinterest about letting others deliver — better security.

Leading browsers are also adopting more robust processes for closing the "patch gap". Since all engines — even the ones given the most care — contain latent security bugs, precautions to insulate users from partial failure (e.g., sandboxing), and the velocity with which fixes reach end-user devices are paramount in determining the security posture of modern browsers. Apple's rather larger patch gap serves as an argument in favour of engine choice, all things equal. Apple's industry-lagging delays are hardly confidence inspiring.

This brings us to the final link in the chain of structural security mitigations: the speed of delivering updates to end-users. Issues being fixed in the source code of an engine's project has no impact on its own; only when those fixes are rolled into new binaries and those binaries are delivered to user's devices do patches become fixes.

Apple's reply hints at the way its model for delivering fixes differs from all of its competitors:

[...] By requiring apps to use WebKit, Apple can rapidly and accurately address exploits across our entire user base and most effectively secure their privacy and security.

[...]

By requiring use of WebKit, Apple can provide security updates to all our users quickly and accurately, no matter which browser they decide to download from the App Store.

Aside from Chrome on Chrome OS (and not for much longer), I'm aware of no modern browser that continues the medieval practice of requiring users download and install updates to their Operating System to apply browser patches. Lest the Chrome OS situation seem like a defence of the iOS position, it's not; the cost to end-users of these updates in terms of time and effort is night-and-day, thanks to near-instant, transparent updates on restart. If only my (significantly faster) iOS devices updated this transparently and quickly!

Unlike browsers on every other major OS, updates to Safari are a painful afair, often requiring system reboots that take tens of minutes, providing multiple chances to re-take this photo.

All other browsers update "out of band" from the OS, including the WebView system component on Android. The result is, that for users endowed with equivalent connectivity and disk space, out-of-band patches are installed on the devices significantly faster.

This makes intuitive sense: iOS updates are often very large and can disrupt of a device for as much as a half an hour. Users understandably hesitate at these sorts of interruptions. Browser updates delivered out-of-band can be smaller and faster to apply, often without any explicit user intervention. In many cases, simply restarting the browser delivers improved security updates.

Differences in uptake rates matter because it's only by updating a program on the user's devices that fixes can begin to protect users. iOS's high friction engine updates are a double strike against its security posture; albeit ones Cupertino has attempted to spin as a positive.

The philosophical differences underlying software update mechanisms run deep. All other projects have learned through long experience to treat operating systems as soft targets that must be defended by the browser, rather than as the ultimate source of user defence. To the extent that the OS is trustworthy, that's a "nice to have" property that can add additional protection, but it is not treated as a fundamental protection in and of itself. Browser engineers outside the WebKit and Safari projects are habituated to thinking of OS components as systems not designed for handling unsafe third-party input. Mediating layers are therefore built to insulate the OS from malicious sites.

Apple, by contrast, tends to rely on OS components directly, leaning on fixes within the OS to repair issues which other projects can patch at a higher level. Apple's insistence on treating the OS as a single, hermetic unit slows the pace of fixes reaching users, and results in reduced flexibility in delivering features to web developers. While iOS has decent baseline protections, being unable to layer on extra levels of security is a poor trade.

This arrangement is, however, maximally efficient in terms of staffing, as it means less expertise is duplicated across teams, requiring fewer engineers. But is HR cost efficiency for Apple the most important feature of a web engine? And shouldn't users be able to choose engines that are willing to spend more on engineering to prevent latent OS issues from becoming security problems? By maintaining a thin artifice of perfect security, Apple's iOS monoculture renders itself brittle in the face of new threats, leaving users without the benefits of the layered paranoia that the most secure browsers running on the best OSes can provide.[3] As we'll see in a moment, Apple's claim to keep users safe when using alternative browsers by fusing engine updates to the OS is, at best, contested.

Instead of raising the security floor, Apple has set a cap while breeding a monoculture that ensures all iOS browsers are vulnerable to identical attacks, no matter whose icon is on the home screen.

Introducing Apple to developer.apple.com #

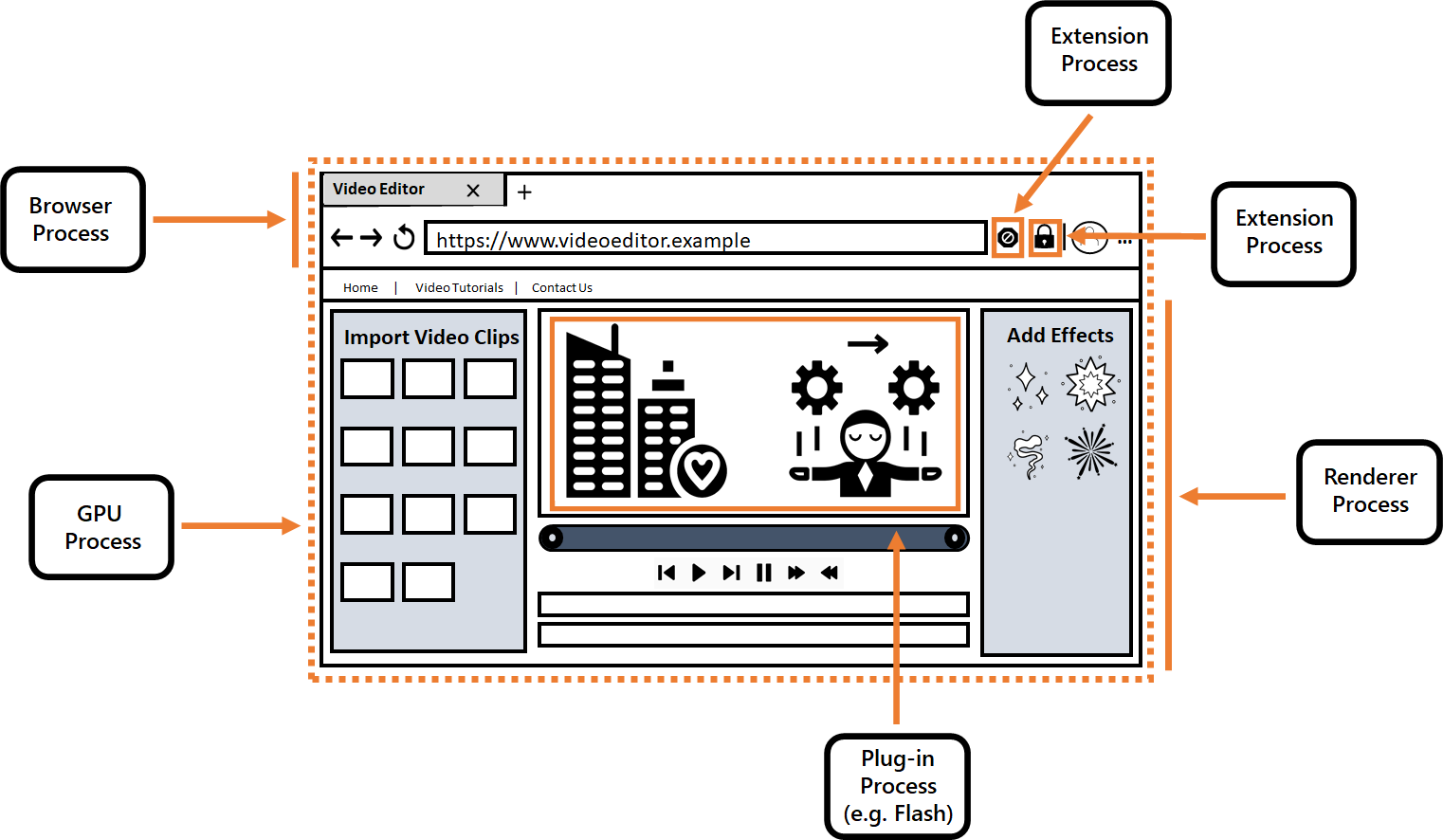

Given Apple's response to Congress, it seems Cupertino is unfamiliar with the way iOS browsers other than Safari are constructed. Because it forbids integrated browsers, developers have no choice but to use Apple's own APIs to construct message-passing mechanisms between the privileged Browser Process and Renderer Processes sandboxed by Apple's WebKit framework.

These message-passing systems make it possible for WebKit-based browsers to add a limited subset of new features, even within the confines of Apple's WebKit binary. With this freedom comes the exact sort of liabilities that Apple insists it protects users from by fixing the full set of features firmly at the trailing edge.

To drive the point home: alternative browsers can include security issues every bit as severe as those Apple nominally guards against because of the side-channels provided by Apple's own WebKit framework. Any capability or data entrusted to the browser process can, in theory, be put at risk by extensions. Even more worrisome is that these extensions are built in a way that is different to the mechanisms used by browser teams on every other platform. This means that any browser that delivers a feature on every other platform, then tries to bring it to iOS through script extensions, has now doubled the security analysis surface area. None of this is theoretical; needing to re-develop features through a straw, using less-secure and more poorly tested and analyzed mechanisms, has led to serious security issues in alternative iOS browsers over the years. Apple's policy, far from insulating responsible WebKit browsers from security issues, is a veritable bug farm for the projects wrenched between the impoverished feature set of WebKit and the features they can securely deliver with high fidelity on every other platform.

This is, of course, a serious problem for Apple's argument as to why it should be exclusively responsible for delivering updates to browser engines on iOS.

The Abandonware Problem #

Apple cautions against poor browser vendor behaviour in its response, and it deserves special mention:

[...] Also, allowing other web browser engines could put users at risk if developers abandon their apps or fail to address a security flaw quickly.

Ignoring the extent to which WebKit represents precisely this scenario to vendors who would give favoured appendages to deliver stronger protections to their users on iOS, the justification for Apple's security ceiling has a (very weak) point: browsers are a serious business, and doing a poor job has bad consequences. One must wonder, of course, how Apple treats applications with persistent security issues that aren't browsers. Are they un-published from the App Store? And if so, isn't that a reasonable precedent here?

Whatever the precedent, Apple is absolutely correct that browsers shouldn't be distributed without commitments to maintenance, and that vendors who fail to keep the pace with security patches shouldn't be allowed to degrade the security posture of end-users. Fortunately, these are terms that nearly every reputable browser developer can easily agree to.

Indeed, reputable browser vendors would very likely be willing to sign up to terms that only allow use of the (currently proprietary and private) APIs that Apple uses to create sandboxed renderer processes for WebKit if their patch and CVE-fix rates matched some reasonable baseline. Apple's recently-added Browser Entitlement provides a perfect way to further contain the risk: only browsers that can be set as the system default could be allowed to bring alternative engines. Such a solution preserves Apple's floor on abandonware and embedded WebViews without capping the potential for improved experiences.

There are many options for managing the clearly-identifiable case of abandonware browsers, assuming Apple managers are genuinely interested solutions rather than sandbagging the pace of browser progress. Setting high standards has broad support.

Just-In-Time Pretexts #

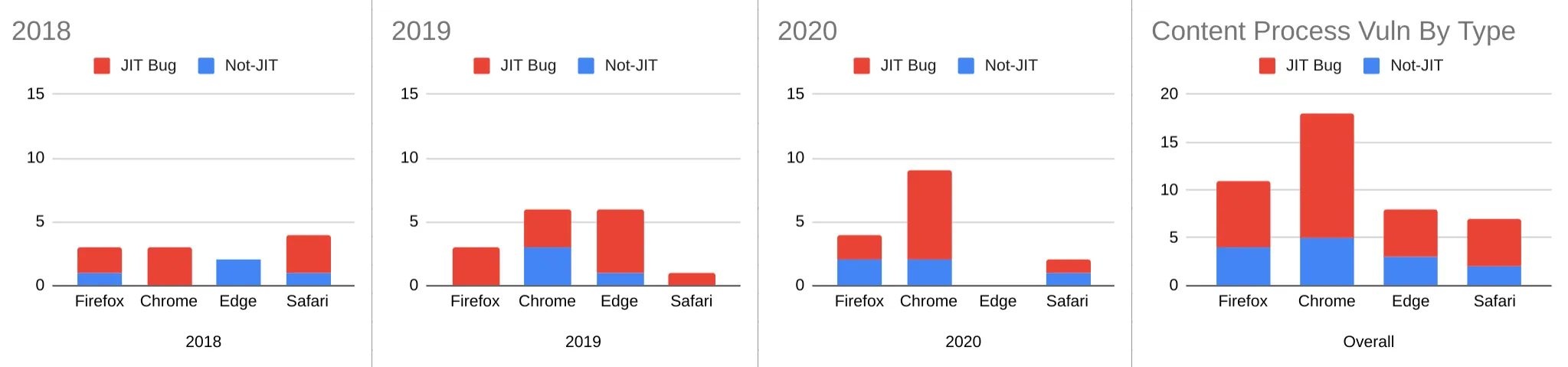

An argument that Apple hasn't made, but that others have derived from Apple's App Store Review Guidelines and instances of rejected app submissions, including Just-In-Time Compilers (JITs), has been that alternative browser engines are forbidden on iOS because they include JITs.

The history of this unstated policy is long, winding, and less enlightening than a description of the status quo:

- All major browser engines support both a JIT "fast path" for running JavaScript, as well as an "interpreted mode" that trades a JITs large gains in execution speed for faster start-up and lower memory use.

- JIT compilers are frequent sources of bugs, and a key reason why all responsible browser vendors put code downloaded from the web in sandboxes.

- Other iOS applications can embed non-JITing interpreters for JavaScript, if they like.

- Safari on iOS has been endowed with JIT for many years, whereas competing browsers were prevented from approaching similar levels of performance. More recently, WebView browsers on iOS have been able to take advantage of WebKit's JIT-ing JavaScript engine, but are prevented from bringing their own.

In addition to WebKit's lack of important JavaScript engine features (e.g. WASM Threads) and protections (Site Isolation), Apple's policy makes little sense on its visible merits.

Obviously, the speed delivered by JITs is important in browser competition, but it's also a fallacy to assume competitors wouldn't prefer the freedom to improve the performance, compatibility, and capabilities of the rest of their engines because they might not be able to JIT JavaScript. Every modern browser can run without a JIT, and many would prefer that to being confined to Apple's trailing-edge, low-quality engine.

So what does the prohibition on JITs actually accomplish?

As far as I can tell, disallowing other engines and their JIT-ing JavaScript runtimes mints Apple (but not users) two key benefits:

- Allowing other engines would mean providing access to the currently-private APIs that allow the creation of sandboxed subprocesses.[4]

- Re-using the WebKit binary maximizes the sharing of "code pages" across processes. Practically speaking, this allows more programs to run simultaneously without the need for Apple to add more RAM to their devices. This, in turn, pads Apple's (considerable) margins in the construction of phones.

Blessing Safari as the only app allowed to mint sandboxed subprocesses, while preventing other from doing so, is clearly unfair. This one-sided situation has persisted because the details of sandboxing and process creation have been obscured by a blanket prohibition on alternative engines. Should Apple choose (or be required) to allow higher-quality engines, this private API should surely be made public, even if it's restricted to browsers.

Similarly, skimping on RAM in thousand-dollar phones seems a weak reason to deny users access to faster, safer browsers. The Chromium project has a history of strengthening the default sandboxes provided by OSes (including Apple's), and would no doubt love the try its hand at improving Apple's security floor qua ceiling.

The relative problems with JITs — very much including Apple's — are, if anything, an argument for opening the field to vendors who will to put in the work Apple has not to protect users. If the net result is that Cupertino sells safer devices while accepting a slightly lower margin (or an even more eye-watering price) on its super-premium devices, what's the harm? And isn't that something the market should sort out?

High-modernism may mean never having to admit you're wrong, but it doesn't keep one from errors that functional markets would discipline. You only learn about them, however, at the greatest of delays.

Diversity Perversity #

A final argument made by others, (but not by Apple who surely knows better), is that:

- Diversity in browser engines is desirable because, without competition, there is little reason for engines to keep improving.

- Apple's restrictions on iOS ensure that a heavily-used engine has a different codebase to the growing use of Blink/Chromium in other browsers.

- Therefore, Apple's policies are — despite their clear restrictions on engine choice — promoting the cause of engine diversity.

This is a slap-dash line of reasoning along several axes.

First, it fails to account for the different sorts of diversity that are possible within the browser ecosystem. Over the years, developers have suffered mightily under the thumb of entirely unwanted browser diversity in the form of trailing-edge browsers; most notably Internet Explorer 6).

The point of diversity and competition is to propel the leading edge forward by allowing multiple teams to explore alternative approaches to common problems. Competition at the frontier enables the market and competitive spirits to push innovation forward. What isn't beneficial is unused diversity potential. That is, browsers occupying market share but failing to push the state of the art forward in any meaningful way.

The solution to this sort of deadweight diversity has been market pressure. Should a browser fall far enough behind, and for long enough, developers will begin to suggest (and eventually require) users to adopt more modern options to access their services at the highest fidelity.

This is a beneficial market mechanism (despite its unseemly aspects) because it creates pressure on browsers to keep pace with user and developer needs. The threat of developers encouraging users to "vote with their feet" also helps ensure that no party can set a hard cap on the web's capabilities over time. This is essential to ensure that oligopolists cannot weaponise a feature gap to tax all software. The effect is to re-privatise standards-based low-level features and APIs by making them available only through proprietary frameworks and distribution channels while denying them to the web.

Apple's playbook has been to preserve the commons as a historical curiosity. Having blockaded every road to upgrading the web, Apple have made it impossible for an open platform to keep pace with Apple's own modern-but-proprietary options. The game's simple once pointed out, but hard to see at first because it depends on consistent inaction. This sort deadweight loss is hard to spot on short time horizons. Disallowing competitive engines that might upgrade the carrying capacity of freely-available alternatives may have been accidental at introduction of iOS, but it's value to Apple now can scarcely be overstated. After all, it's hard to extract ruinous taxes on a restive population with straightforward emigration options. No wonder Cupertino continues to perform new showings of the "web apps are a credible alternative on iOS!" pantomime.

In this understanding, the web helps maintain a fair market for software services. Web standards and open source web engines combine to create an interoperable commons across closed operating systems upon which services can be built without taxation; but only to the extent it's capable enough to meet user needs over time. Continuing to bring previouly proprietary features into the commons is the core mechanism by which this progress is delivered. Push notifications may have been new and shiny in 2011 but, a decade later, there's no reason to think that a developer should pay an ongoing tax for a feature that is offered by every major OS and device. The same goes for access to a phone's menagerie of sensors, as well as more efficient codecs.

The sorts of diversity we have come to value in the web ecosystem all live at the leading edge. Intense disputes about the best ways to standardize a use-case or feature are a strong sign of a healthy dynamic. It's rancid, however, when a single vendor can prevent progress across a wide swathe of domains that are critical to delivering better user experiences, and suffer no market consequence.

Apple has cut the fuel lines of progress by requiring use of WebKit in every iOS browser; choice without competition, distinction without difference. Users can have any sort of web they like, so long as it's as trailing-edge as Apple likes.

The sorts of diversity we have come to value in the web ecosystem all live at the leading edge. Intense disputes about the best ways to standardise some use-case or feature are a strong sign of a healthy dynamic. It's rancid, however, when a single vendor can prevent progress across a wide swathe of domains that are critical to delivering better user experiences and suffer no market consequence.

Yet this sort of participation-prize diversity is exactly what some (purported) defenders of Apple's policies would have us believe is, instead, healthy for the web.

It's a curious sort of argument. It seems to admit that Apple's engine is deeply sub-par (which it is) by way of excusing future failure to compete. It's not as though Apple is wanting for the funds and talent to build a competitive engine, however. It simply chooses not to. Apple's 2 trillion dollar market cap is paired with nearly $200 billion in cash on hand. One could produce a competitive browser for the spare change in Cupertino's Eames lounges.

Claims that foot-dragging must be protected because otherwise capable engines might win share is inadvertently back-handed. Excusing poor performance is to suggest that Apple does not possess the talent, skill, and resources to ever construct a competitive web engine. I, at least, think better of Apple's engineering acumen than do many of these nominal defenders.

More confusingly, it's unclear whether or not there should be any eclipse of WebKit in the offing, even if Apple were to allow other engines onto iOS while continuing to take up the rear on features, performance, and standards conformance. We have a natural experiment to this effect in Safari for MacOS. It continues to enjoy a high share of the Mac browser market despite stiff and legitimate browser competition on MacOS. Are Apple's defenders so certain that this won't be the natural result should iOS eventually provide a fair marketplace for browsers?

What is the worst-case scenario, exactly? That Safari loses share and Apple must respond by funding the WebKit team adequately? That the Safari team feels compelled to switch to another open source rendering engine (e.g. Gecko or Blink), preserving their ability to fork down the road, just as they did with KHTML, and as the Blink project did with WebKit?

None of these are close ended scenarios, nor must they result in a reduction in constructive, leading edge diversity. Edge, Brave, Opera, and Samsung Internet consistently innovate on privacy and other features without creating undue drag on core developer interests. Should the Chromium project become an unwelcome host for this sort of work, all of these organisations can credibly consider a fork, adding another new branch to the lineage of browser engines.

All of this has been in Apple's control. It's not a foregone conclusion the world's most valuable tech firm should produce the lowest-quality browser engine. The narratives in this space would surely be different if Apple's coercion about engine choice weren't paired with failure to keep pace across a wide variety of platform areas and features. A festering combination of low-quality and arm-twisting has created the current morass.

The point of diversity at the leading edge is progress through competition. The point of diversity amid laggards is the freedom to replace them — that's the market at work.

End Notes #

Nobody wishes it had come to this.

Apple's polices against browser choice were, at some point, relatively well grounded in the low resource limits of early smartphones. But those days are long gone. Sadly, the legacy of a closed choice, back when WebKit was still a leader in many areas, is an industry-wide hangover. We accepted a bad deal because the situation seemed convivial, and ignored those who warned it was a portent of a more closed, more extractive future for software.

Only if we had listened.

Thanks to Chris Palmer and Eric Lawerence for their thoughtful comments on drafts of this post. Thanks also to Frances for putting up with me writing this post on holiday.

As we shall see, it would be better for Apple if their "supporters" would stop inventing straw man arguments as they tend to undermine, rather than bolster, Cupertino's side. ↩︎

Browser engines all have a form of selective exclusion of code that is technically available within the codebase but, for one reason or another, is disabled in a particular environment. These switches are known variously as "flags," "command line switches," or "runtime-enabled features."

New features that are not ready for prime time may be developed for months "behind a flag" and only selectively enabled for small populations of developers or users before being made available to all by default. Many mechanisms have existed for controlling the availability of features guarded by flags. Still, the key thing to know is that not all code in a browser engine's source repository represents features that web developers can use. Only the set that is flagged on by default can affect the programmable surface that web developers experience.

The ability of the eventual producer of a binary to enable some flags but not others means that even if an open source project does agree to include code for a feature, restrictions on engine binaries can preclude an alternative browser's ability to provide even some features which are part of the code the system binary could include.

Flags, and Apple's policies towards them over the years, are enough of a reason to reject Apple's feint towards open source as an outlet for unmet web developer needs on iOS. ↩︎

It's perverse that the wealthy users Apple sells its powerful devices to — the very folks who can most easily dedicate the extra CPU and RAM necessary to enable multiple layers of protection — are prevented from doing so by Apple's policies that are, ostensibly, designed to improve security. ↩︎

JIT and sandbox creation are technically separate concerns (and could be managed by policy independently), but insofar as folks impute a reason to Apple for allowing its engine to use this technique, sandboxing is often offered as a reason. ↩︎